“Millions of language students are trapped in vicious circles. They complain that they cannot understand what they read in the foreign language because they do not know enough words. So they do not read and they do not increase their vocabulary, and so they continue not to be able to understand. Then perhaps someone tells them how important reading is and persuades them to try again. So they sit down with their dictionaries, and they look up every single word that is new to them, and very often many words that are not new but that they 'want to be quite sure about'. At the end of three hours they have got through half a page in a book, or half a column in a newspaper. They do this for three or four days, and then give up in despair, oppressed by the tediousness of it all. They are convinced quite correctly that they do not know enough words to understand ordinary books and newspapers. As a result their vocabularies stay more or less the same size as they were, and they complain that they are making no progress. They either become permanently frustrated and depressed, or just give in and give up. And it all happens because they have spent more time with the dictionary than with the language itself.” (Source: Gethin / Gunnemark - The Art and Science of Learning Languages, p. 89)

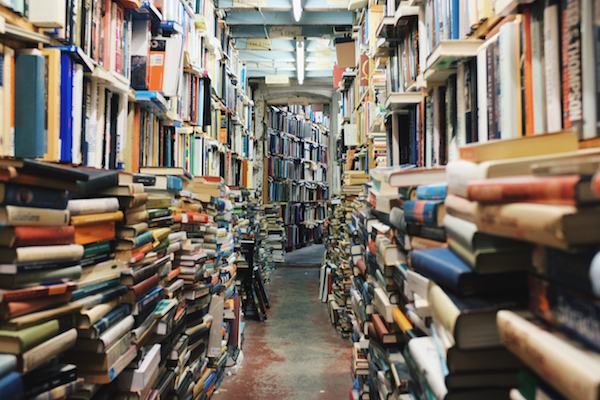

Reading is unjustly maligned. Lots of students of Arabic pass through Amman, Jordan, where I'm currently based, and it's not uncommon to hear the refrain, 'I'm interested in learning how to speak, not to read and write.' This blog post is about how you should be reading, EVEN IF spoken is your ultimate goal. I hope I can convince you of this fact, and entice you with some of the ways reading will enhance your study and understanding of culture and history.

A large part of my book on getting out of the intermediate plateau in Arabic language learning is about the importance of reading.

Reading is the most useful activity to help an Arabic student stuck at the intermediate level. Even if your priority is to be functionally competent in a dialect, reading is still useful because it brings holistic improvements to your language abilities as a whole. The basic approach that I outlined in my book runs as follows:

1) Find good materials

2) Read lots of material at an appropriate level

3) Keep going and be regular

4) Cross-check for performance

Only the final point needs explanation. When you are reading lots of things in Arabic over a period of a few months, you may not be aware of how you are improving, or at what rate. For that reason, it’s worth putting in place some checks and points to review every month or two.

There are a number of different tactics we can use when reading, and I’ll get into the details of these below, but for now you should bear in mind that it helps to switch around the reading tactics that you’re employing every so often. At a very high level, you can shift from deep / intensive reading to wide / extensive reading. You can find ways to write and speak that will help you ‘activate’ the words and topics that you’re learning.

The primary benefit of reading is that it increases your vocabulary. After you’ve done a few years of Arabic study, you will probably realise that the way the language works (particularly the way the verb system supports how words are generated / derived) means you really need to work on your vocabulary if you’re going to emerge into the advanced levels of comprehension. Moreover, the size of this challenge — the number of words, that is — is such that whatever tricks or skills that got you this far aren’t going to be useful or efficient in surmounting the problem.

This is where reading comes in. If you can split the words you know into active and passive categories, reading is immediately helpful in increasing your passive vocabulary. (Active vocabulary are the words that you can produce easily in writing or in conversation, while passive vocabulary are the words that you can recognise when you see them in Arabic, but couldn’t necessarily produce or use them yourself). When you read books at the right level, you can figure out the meaning from the context. (This is how we learn new words and figure out meaning in our native tongues). This will rapidly increase your passive understanding of texts (and, to a lesser extent, things you hear). There is some transfer of these words into your active vocabulary, but that transition is not guaranteed and it usually takes a bit of extra work. This work usually involves writing of some kind.

At its core, the work of increasing your vocabulary comes down to how many times you are exposed to a particular word (or words). The more you are exposed to it, and the more contexts in which this happens, the better that will be for your ability to feel comfortable with the word. For example, if you hear the word for dish in a kitchen, a cafeteria, or in a restaurant, you will remember it when you have to order a meal at a restaurant.

From this perspective, reading is cost-effective and time-efficient. It is much faster to pick up a book and read it than to have to schedule a lesson, or distract someone from what they’re doing. You are also much more likely to find a varied stream of content by using written materials than if you solely rely on conversations or videos.

Being able to read is a valuable skill. Numerous studies have shown that your ability to be professionally useful in a language benefits far more from reading skills than spoken ability. Many people tend to discount reading from their skill set because they feel like it will take them too much time to learn how to read. And even though this book discusses listening and reading practices, reading is key to intermediate Arabic study. By not reading Arabic you are missing out on a great opportunity and a great way to distinguish yourself from your peers. Think what you could do and add to your work, career or discipline if your reading ability in Arabic was as good as that in English.

Reading connects you to other people, generations and eras. It’s the easiest way to mind-read and time-travel on the market! If you’re stuck in a country outside the Arab-speaking world, this is how you can get in touch with people, their culture, their history, their entertainment and all sorts of other dimensions. In terms of efficiency, reading is at the top of the list in this sense.

Reading is a badge of competence, both in how peers see you but how Arabic-speakers perceive you. If you are able to confidently navigate the written word, you’ll have more opportunities, people will take you more seriously and you’ll have a generally better quality of engagement as a result. Given that the way to reach that is enjoyable and — all things being relative — not too time-consuming, it’s harder to see reasons why you wouldn’t want to be reading more.

If a command of dialect / spoken Arabic is important to you, or your writing, perhaps, reading offers a break from that skill work and affords great opportunity for cross-training. The words you learn while reading can and do transfer over to other domains.

Arabic written by professional writers (whether fiction or non-fiction) often has the unfortunate tendency to be very verbose, using multiple synonyms for a similar meaning. In fact, finding an obscure yet beautiful adjective is almost a badge of achievement for many writers, particularly in older generations. This makes taking the dive into authentic reading materials for language students much harder. Luckily, publishers have been busy at this and a large number of intermediate- to advanced-level readers are being released. This is good news as you can now easily bridge the gap between basic textbook sentences and authentic material, whereas this wasn’t as possible even a few years ago. (It wasn’t the case when I first studied Arabic, for example). There are also a number of useful technologically-enabled services which allow you to ramp up and gradually increase this difficulty level. Moreover, you can follow your interests much more, whether you’re interested in fiction, politics or history, there are appropriate materials available. When you don’t read Arabic, you’re actually missing out on this huge conversation and discourse which is happening right this moment - whether its on Twitter or in op-ed columns - and which has been happening for as long as there have been Arabic speakers and writers.

Reading is an incredibly flexible skill to practice. You can do it almost anywhere, using physical books or digital materials. It works for short as well as long time slots, and, best of all, it’s fun! Particularly when you’re working on extensive reading, you can really lose track of time when reading a good novel or following whatever blog covers the topic that really interests you.

[This is the first in a series of posts on the importance of reading in learning Arabic. The next post will summarise an academic study of the role of reading in bringing students up to the highest levels of achievement in their Arabic proficiency.]