I’ve been working to diversify my skills over the past three years, in particular to grow as a software developer / computer programmer. To that end, I started working my way through the Launch School syllabus a few months back. I’m at an inflection point in the course right now so I thought it worth reflecting on what study habits have served me well as well as which ones I still haven’t quite managed to adopt.

Before I started, I exhaustively read through their forum comments and in-house blog posts to see how I might best approach my study time. They recommend you spend 20+ hours per week working on their course materials. With such a large investment of my time, I wanted to make sure I was getting the best return.

Core principles / Mental Models

- ‘Get Good at the Fundamentals’

This is a bit of a mantra at Launch School and I find it greatly appealing as a principle to drive how I study. It’s also useful as a heuristic to decide whether to dive deep on something, to read an article, to attend a meetup and so on. (See more here.)

- ‘Process, not goals’

I’m not sure I saw this explicitly enunciated somewhere, but given the fact that it can take around two years to work your way through the syllabus it seemed useful to keep in mind. I already have adopted this thanks to Beeminder and a really excellent piece by Scott Adams from 2013. With a somewhat long-term goal, arbitrary goal-focused time deadlines (‘finish the 202 course by May’) are less useful than something where you specify the amount of time you’d like to regularly invest into the study process.

- ‘Finishing is not the goal, mastery is.’

There’s a little bit of fetishising the idea of ‘mastery’ at Launch School, but this principle reminds me not to be in so much of a rush while working through the course. As Chris Lee mentioned in the forums, “if you’re in a rush, my question is: “where are you going?””

- (Find ways to) enjoy what is hard

This one I find quite difficult, lazy and averse to struggling with difficult things as I am. The whole skill/career of coding and wrestling with these abstract concepts in your head is one where you’re constantly upgrading your baseline of difficulty. This is rewarding in that there are always challenging problems to chew down on. This is also frustrating, though, because there’s always somewhere harder / out of reach to work towards. A number of students and TAs on the forums mentioned that having a mindset where you actively seek out those moments as opportunities for growth was a game-changer for them. (Note: strong intersections with Dweck’s growth mindset here).

Mindset

- Abandon artificial timelines

Don’t work to get through a course in x or y number of months ‘just because’. Rather, only advance if you’ve actually mastered the things in that course. This is a freeing perspective to take if you can find a way to adopt it. Society / culture encourages always keeping an eye on the clock, so this is a hard one (for me at least).

- Comparisons are odious

It doesn’t help to compare timelines. Everyone is coming at things with a different background and set of experience behind them. It also doesn’t help to compare competency / progress through the course for the same reason. It adds very little to my ability to grasp a particular topic to know where I lie on the bell curve. The only slight exception to this is knowing that the full core curriculum will take somewhere between 6-24 months to complete; this way if I am still studying it 20 years from now I can maybe recalibrate.

- Lean in to hard problems

I covered this earlier. If I have it as a sort of rubric which reminds me to lean into the difficulty whenever I encounter such a patch, then that’s useful.

- Master the current problem in front of you, right at this moment, without anxiety

Books are written one word at a time. Similarly with logic problems, or broken code or whatever, taking a calm look at something that looks knotted and gnarly is the way to approach it. There’s no need for anxious sudden movements, or huge massive changes. Work your way through things one step at a time.

- Be clear about the ‘why’

For something that isn’t completed quickly (i.e. within a few days), it pays to remember why you’re doing it. This helps with motivation, it helps reorient you to what kinds of choices you have to make, and it (often) helps remind you of some best practices around working towards that mastery.

- (Be specific)

This is sort of a sub-point relating to specifying the reason why you’re doing something. Try to specifically connect with some kind of emotion, visualise the outcome in some kind of image etc; this will help get the most of your reasons why in terms of it translating into motivation and clarity of purpose.

Practice

- Study ‘to depth’

Make sure to study the exercises or problems to their full depth rather than just completing them for the sake of moving on. A useful image to have in your mind is that of squeezing an orange. You don’t want to abandon the orange (i.e. the opportunity to study a particular problem) until you’ve squeezed every last drop out of it. There’s a point at which you’ve spent too much time, of course, but for many / most people you’re likely erring on the side of ‘making progress’ vs getting lost going too deep.

- Do code exercises

There’s lots of options for this. You probably don’t want to start out doing this when you’re still figuring out what a variable is, but fairly soon it pays to get into the habit of doing an exercise or three each day. Think of it almost like your daily workout. You’re building your muscle memory for solving problems, as well as cementing various syntactic and idiomatic phrasings. Of course, Launch School has you doing a mountain of exercises as well, so don’t worry too much about supplementing from outside the course, at least not initially.

- Reinforce concepts / theories using active recall

This is learning meta-methods 101, but always worth reminding oneself to actively test yourself. Don’t just read through notes, but keep a list of higher-level concepts or method names and then take 30 minutes or an hour once a week to type out an example or two using each of those concepts and methods. (More on this later).

- Deliberate practice

This builds on the previous concept of active recall. For me, this often takes the following shape: I’ll complete an exercise or a challenge. Perhaps I’ve solved the problem fine using my own code / approach, but when I finish and look at the ‘official’ solution it differs from mine in some (big or small) way. I’ll take a look, make sure I understand the principles around which it’s organised, then I’ll shut that page / window and try to replicate that approach myself. Sometimes, if a problem was hard enough to solve, I’ll even leave it a few days and just try to work the problem from scratch in any possible way that I can think of. I have enough of a goldfish brain that sometimes this will feel like I’ve never solved the problem in the past.

- Compare solution tradeoffs

Alongside just trying to code it from scratch yourself, it sometimes helps to compare the various approaches (perhaps adding in solutions given by other students) and seeing which might be optimum. Asking ‘why’ at this point is often a useful place to stretch towards, even though the answer to that ‘why’ is often a few modules ahead of where you are. I keep a log of these bigger picture ‘why’ questions.

- Build things

Perhaps slightly controversial amongst those taking Launch School. They don’t encourage a ‘hack and slash’ mentality but rather direct towards a more methodical and deliberate approach. That said, once you’re at a certain point, it can be useful, motivating and just practically beneficial in terms of the reps it gives you, to build something that has meaning for you or for others. At the moment I’m just working on somewhat more pure Ruby code in the terminal / via the command line, but later on I imagine this will become more relevant. (To that end, perhaps keep a list of project ideas).

Taking Notes / ‘Studying’

This is the one that people seem to have the most thoughts about on the Launch School forums. That’s possibly explained by the fact that people will know what works for them — or at least will have some patterns that they feel have worked for them in the past, in somewhat analogous situations.

- Type out all code examples manually

This one is easy to forget. When you’re following along with a video or textbook, make sure to type out the examples, however easy or seemingly comprehensible they seem. Typing not only engages your muscles, giving you an additional hook for memory, but it forces you to slow down and gives an opportunity to question what each character of a code snippet is doing.

- Take notes with pen and paper first time round

This is especially true for things that I’m not fully comfortable with. For something where I have thousands of hours of experience under my belt — the modern political history of Afghanistan, let’s say — I have more of a structure in my head and so can get away with typing notes. For the rest, like all these new things I’m learning about Ruby, pen and paper is pretty unbeatable. There’s a bunch of good science confirming that that’s the case, and it aligns with my experiential sense as well.

Some people in the forums noted how one of their preparatory tasks prior to an assessment was to type up their handwritten notes into a more formal digital reference of the course materials. I’m in two minds as to whether I think that’s going to be useful, mainly because the online documentation exists to serve that purpose. But I’m at the point where I have to decide about that so watch this space…

- Anki for things you need to remember

If I think a particular method / fact / morsel of knowledge is something I’m going to want to actively recall from memory in the future, I’ll add it to Anki. I try to follow the principles outlined in Piotr Wozniak’s essential piece entitled “Twenty rules of formulating knowledge”. (Seriously if you use Anki and you haven’t read it, stop right now and go read it).

I use a mix of cloze-deletion cards and custom templates for coding.

This card is a simple cloze deletion card. I wanted to make sure I was learning the options for file permissions as part of the command line portion of the prep course.

This card tests my ability to produce an example where I’m using the .reduce method. I try to include a bunch of these production cards since they mimic the kinds of situations / circumstances where I’d need to recall this piece of information in real life.

[Even though comparisons are odious (see above), in case it’s of interest to others, I’m just through RB101 and about to begin RB109 and I have 536 cards that I generated during the course of my studies.]

- Ask questions

Ask lots of questions. The advice given by Launch School instructors is to focus on the why questions when asking others. (The how questions are usually a matter of looking something up). I found this was broadly true. I have a reserved set of pages at the end of my notebook where I write down these questions that seem a bit outside my comfort zone.

Some of these get answered in the course of the programme. For example, I see that one of my questions was about why symbols are often preferable to non-symbols when used as hash keys. This was answered (sort of / enough to give me a sense of the answer) a few lessons later. Others are bigger issues for which there probably is no final answer. For example: “doesn’t dynamic typing force us to spend a lot of time validating input? isn’t static typing safer?”

Asking ‘why’ something behaves they way it does allows you to better develop your mental models and can be an effective way to grasp what’s going on.

- Feynman technique

I use a slight variant of this much-lauded technique. It consists of something approximate to the following steps:

- Write the title of a topic that you want to study / test yourself on

- Write or map out an explanation of that subject intelligible / appropriate to a non-specialist. Do this from memory.

- Identify any gaps in your explanation / understanding.

- Relearn / restudy / interrogate to fill in the gaps.

You can use narrative / diagrams to condense and clarify your explanation. For my Launch School studies, I do this once a week on Saturdays. I keep a list of new methods that I’m learning about during the week. Particularly towards the end of RB101 these started to mount up. Then on the weekend, I’d take the list of methods and test myself by writing out (by hand, with pen and paper) code that illustrated how to use each method. If needed, I’d write or say out loud an explanation relating to that method. This is a humbling exercise; you realise that you don’t know the things that you thought you knew.

- Write blog posts to explain anything that feels unclear

My last blog post is an illustration of this. I was having trouble getting what the .zip method could be used for and how it transformed things to which it was applied. So I wrote up some notes to myself in the form of a blog post.

I sometimes worry that too many of these posts — written purely for me to understand something — are alienating for those who subscribe to the blog via something intrusive like the email newsletter. I considered putting my ‘writing for the purposes of understanding’ posts in a separate location. In the end, though, I’m probably overthinking it. Like it or lump it!

- Make mental models of how things work

A lot is made of this, both at Launch School and in the wider world of study techniques. I’m not sure I have too many examples of where I’ve formally had to think through something using a mental model of how it works. I imagine this will start to be more applicable in later courses. Or perhaps it’s just that I already have some mental models for how the code behaves owing to my previous studies in coding. At any rate, I’m keen to get the most out of this but so far haven’t found it to apply too much.

- Make a cheat sheet at the end of a topic

I haven’t done this yet, though I can see how it’d be useful. For my current course and assessment, I think it’s probably hard to do — i.e. condensing the Ruby language to a single sheet of paper. But I’m reserving the right to do this at a later stage.

- Spend time reading the code of others

I tried to do this a little bit while going through the exercises. My hesitation was initially that the code hadn’t been reviewed or formally assessed and I didn’t want to absorb bad patterns from others who — like me — were likely at the beginning of their journey and who couldn’t be expected to know if they were writing something that should be emulated or not.

In the end, I think it’s still useful to read the code of others. It’ll usually be somewhat clear or not whether an answer is overly complicated. And answering why you think that is in itself a revealing process.

Review

The Launch School syllabus takes a year or two to get through. You start off with Ruby, but later on you’re working on Javascript or whatever. The concepts and the methods and the details could easily start to get forgotten if you’re not regularly reviewing and practicing things you studied in the past.

- Anki as the cornerstone for spaced repetition

As evidenced by the large number of cards in my Anki deck, Anki occupies a central place in my strategy to outsource the need to worry about reviews and recall over the long-term. If there’s something I want to be able to recall a year from now and it’s not something I’m using literally every day or two, then it’s going to end up in Anki.

An important note, though: learn the material FIRST, before adding it to Anki. I’ve learned this the hard way in the past; if you don’t learn it before adding to Anki, you’ll find Anki becomes slow and filled with a sense of drudgery. It’s also inefficient to group those two very separate tasks into a single moment at the point where you’re reviewing a card.

The great thing about Anki is that as a particular fact passes from your short term memory to your long-term memory, the need for reviews becomes less frequent, so you’ll see it less often. Trust the spaced repetition algorithm. It knows what it’s doing.

- Explain a concept out loud

This overlaps with the Feynman technique (see above). You can do this on your own, or to a friend / captive audience. Doing this with people who are much older or younger than you can be instructive as to whether you actually understand a particular topic.

I sometimes build this in as part of my Anki studies. I’ll have a card where the front says “What is [concept x or whatever]? Try explaining it out loud.” Then I’ll either find someone to do this with or I’ll just do it myself. Then on the back of the card it’ll either have a small list of key sub-concepts to make sure I got it right or it’ll say “Go look at your notes to confirm that you covered everything important”. This way I’m getting prompts to review old material, but they’re reoccurring at regular enough intervals that I don’t have to worry about having to do this too often.

- Keep Ruby / other fundamentals sharp

People in the forums mentioned that when they moved on to Javascript or other parts of the course, they found their Ruby skills starting to atrophy. Many said they wished they’d been more formal about reviewing old materials and keeping those skills fresh.

I think this is best solved by doing regular code challenge exercises as provided by sites like those listed above. I’ll use Beeminder to keep me honest and doing at least one or two every few days.

- Review old materials

People suggested that roughly 20% of your weekly study time should be devoted to reviewing old materials. I wonder if that’s a little high, but for me that might translate to keeping a solid hour or two on Saturdays for review of those old materials. And by review I mainly mean active recall using some of the techniques mentioned above, and then reading through notes to confirm whether I still knew something or not.

Getting Stuck

This is where I struggle the most with coding — the mental game of failure. But having a process to deal with those moments — because they will come — addresses a good chunk of the issue when it comes to getting stuck. The following are possible options for working through it, as suggested by fellow students / instructors:

- Read the error messages thoroughly

- First try it with pseudocode

- Solve problems on your own before looking at solutions or asking others for help. (If you can’t solve it, and depending on the size of the problem, still don’t look at the solution until a day or two has passed).

- Use the rubber ducky method of talking through a problem. (This can be translated to writing as well, where just the act of writing up where you’re stuck can often be enough to get you unstuck)

- Don’t cheat yourself of the opportunity to learn if the problem is difficult. Work through it and take your time.

- Use the PEDAC system / process

Community

Everyone studying at Launch School is doing so remotely. We’re all scattered around the world, but doing thing with others can be really helpful with motivation. I don’t always find it the most time-efficient way of studying, but working with others in a structured manner seems to be strongly recommended by posters in the forums. For me I think this will take two forms: attending the group study sessions appropriate to my particular level, and interacting with discussions on the forums and Slack channel.

I might supplement this with ad hoc study groups depending on my need for that during assessment preparation. At any rate, there seems to be a good deal of opportunity for that kind of thing among fellow students.

Habits / Meta-Structure

A lot of this comes under the rough category of ‘life fundamentals’. Most shouldn’t need too much explanation.

- Stop using / viewing social media or meaningless input — for me that’s Twitter and YouTube. I have turned this off completely outside specific windows.

- No email — I also have email turned off everywhere except outside certain windows. On my phone, I’ve set it up that I don’t have access to IMAP mail via apps or the standard ‘Mail’ app, but I am able to send mails through SMTP email.

- Be careful with caffeine / tea — I don’t drink coffee, but some varieties of tea cause me to get a little too edgy and scatter-brained. So this is just a reminder to be conscious of that and always err on the side of caution. Also, periodically taking 1-3 weeks completely without caffeine (as with salt) allows me to reset my baseline, needing less to cause the stimulating effect it has.

- Keep the house / room clean

- Go for a walk every day

- Exercise — do it.

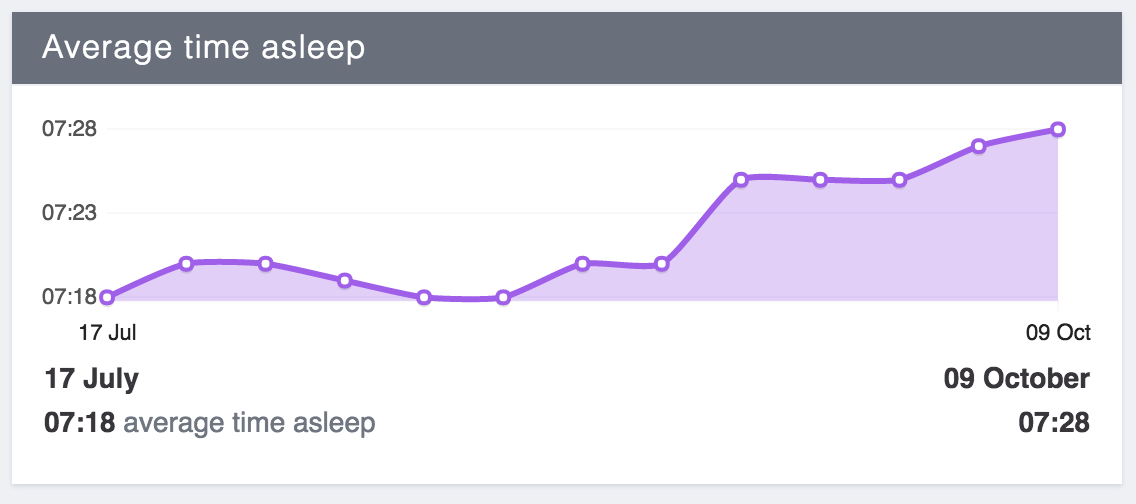

- Sleep — this is maybe the most important item in this entire post for me.

Scheduling Study / Core Routine

- Study Every Day

I try to study a minimum of two hours every day on average, moving up to a stretch goal of three or four if I am able. This allows me to make meaningful progress in my studies. Ideally, I try to have at least one day / week which is a 3-4 hour uninterrupted slot. But probably four hours is my maximum when it comes to focused, productive work.

- Pick a sustainable pace

I could probably do a few days of full-on / flat-out work, but eventually I’d burn out. The trick here is to do enough that you can always work the next day. This means not working from a place of exuberance or excitement. Learning and coding doesn’t have to be high-octane. That doesn’t mean it can’t be enjoyable or satisfying, needless to say.

This means starting with reasonable weekly hours and slowly increasing them rather than jumping straight into an intense pace of 5 hours a day, let’s say.

For me, this initially looked like starting with 15 hours per week and I’m currently at around 18. Reaching somewhere around 25-30 would be my ideal, but I have to listen to how my mind and body responds, and have to balance other work to support (read: pay for) this course of study.

- Create a routine / habit around Launch School study

For me, this means having my studies as the first thing I do in the day. I want to give it the time when I’m at my best during the day, so that means first thing in my morning. I potter around for 30-60 minutes after getting up, and then I immediately start work on my studies.

- Block things

I covered this above a little, but basically for me it means using tools like Freedom and Focus apps to keep me honest and not distracted. I’m fairly good about using these tools, but not always and it’s easy to notice the difference.

- Take breaks

I usually segment my studies with inbuilt short breaks. These can be anywhere from 5-10 minutes and I try to get up, stretch or do some kind of physical exercise / movement. For Macs, the Move! app is a great utility. I like to take somewhere between one and two breaks per hour on average.

- Think about posture early on

This is something which I haven’t thought too much about, but people on the Launch School slack channel and elsewhere have suggested it’s important. If you’re going to spend hours behind some sort of laptop, getting posture and ergonomics right seems like a good thing to aim for. I’ve had good experiences with the Ninja Standing Desk (sadly not being produced any more, it seems!) though I don’t currently have it with me. This is something to return to in a few months.

- Take a day off

I take one day off each week which is for non-tech things, or family or friends. This is usually Saturdays for me but not always. I turn off phones and laptops and don’t let myself use them for the whole twenty-four hour period. I sometimes lose this habit when I have too many things going on and am overcommitted — witness that I’m currently writing this blogpost on my supposedly sacred Saturday ‘day off’ — but in any given year I’ll stick to it perhaps 80% of the time. The more I work on Launch School the more I’m reminded that it’s a good thing to disconnect from digital input and reconnect with the world around me.

- A routine for the end of the day

Currently the two key parts to this involve writing down what’s coming up tomorrow and where to start with them. It also includes making my environment conducive to just starting work the next day — i.e. cleaning my desk.