[UPDATE: I now offer one-on-one language coaching designed to help students prepare for Middlebury's intensive summer programme. Read more about what it involves and what kinds of problems it's best suited to addressing.]

[UPDATE 2: (Jan 2017) I've just finished writing a new book, Master Arabic, on getting from an intermediate level in Arabic to advanced. Read more here.]

I returned from my summer course in Middlebury a few weeks ago, and I thought it might be worth writing up a few of my thoughts about the programme, whether I’d recommend it to others studying Arabic (and other languages) along with some other more practical tips for students who will be joining the summer programme in the future.

Overall, I had a good time and I learned a lot. I think that alone should be sufficient recommendation. It’s two months where you get to study something to the exclusion of everything else, so in that sense it’s a real chance to focus, to immerse yourself in the skill. To some extent, the programme almost could have been anything at all and students would benefit, especially if you’re able to work alone and at the level where you’re able to profit from self-directed study. I can’t remember the last time when I focused on one thing and one thing only over a period of two months. I was also really lucky to have two excellent teachers leading our class, and to have been awarded one of the we-pay-for-everything Kathryn Davis fellowships; for both, I’m extremely grateful.

You can read more about the programme itself here but basically, it’s an eight-week programme of intensive language instruction and practice. They implement a language pledge (to read more about my implementation of that, read this) which means for the entire duration you’re not supposed to talk or use any other language than your target language (Arabic, in my case), even when outside the classroom. I took it a step further and stopped using anything other than Arabic on twitter, email and so on.

One of the interesting (sometimes frustrating) features of the Arabic language is the so-called 'diglossia' (and here). This means that the language used in writing and in conversation in the mass media and among educated Arabs is different from the more colloquial spoken or dialect version of the language. For the beginner, this is a frustrating realisation, especially since so few programmes and textbooks seem to place much emphasis on learning the colloqial/spoken part of the language. When I studied at SOAS (the BA Arabic programme) there was virtually no emphasis placed on the dialect, aside from the year abroad (which I spent in Damascus and thus had some contact and exposure to the Syrian / shami dialect). In any case, I was expecting that the Middlebury course would have more to offer in terms of dialect tuition, especially having spent hours reading their website and course syllabi, but this was not the case. There are dialect classes four days per week, but they are not taught to any particular syllabi and it very much is a question of chance as to whether your teacher knows how to teach (and encourage the practice of) their dialect or not. The only thing I’d say, though, is that there are lots of varieties on offer, from the more common Egyption and shami to Jordanian, Moroccan and even Sudanese. Anyway, this is all just a warning to say probably don’t go to Middlebury if all you care about is developing a really good set of spoken skills.

Students take a long placement exam the day after they arrive, and then the 140-or-so of them are split into levels. Normally four is the highest level offered, but this year they added 4.5 to accommodate people who had slightly longer experience/exposure. (I was in that class).

Formal classes run from 8.45am-1:15pm (with some 5-15 minute breaks in-between to space it up) followed by lunch. After lunch, there are colloquial / dialect classes for an hour, and then you more or less spend the rest of the day doing assigned work in preparation for the next day, revision of the work you did that day and other kinds of homework. I think the teachers estimate that you should be doing four or five hours of work outside class every day, or that’s what they aim to provide/assign. That’s what’s meant by the whole "intensive" part of the Middlebury programme. (For more on whether I found the intensity of the programme useful, see below).

What follows consists of recommendations for those planning to take the programme in the future. It’s mostly things I did while I was on the course, but there are some things that I’ve since realised would have been useful as well or instead of the approach I took. Feel free to pick and choose which sections you read, as they’re all meant to more or less stand alone, depending on your interest.

Preparation

I’ve already written up some thoughts, here, on what I did before the programme started to ensure that I wasn’t just revising things I had already studied. My case was perhaps unusual in that I had a long period of (somewhat-focused) study under my belt in terms of my BA degree, but years of non-use meant that I didn’t really feel confident using the language any more.

Why is it useful to do some extra study before the start of the course? I’m going to take it as a given that you’re not a complete beginner, in which case, you more or less know what you need to be studying: a little bit of grammar perhaps, lots and lots of words, lots of spoken practice, a decent amount of reading at the appropriate level, and so on. So why not get a headstart and do some study beforehand so you can benefit from the focused months coming your way?

If you’re a complete beginner, there’s still a lot of value in doing some work before the programme starts. A lot of the things you do in the early days of learning Arabic are somewhat menial (learning the alphabet, practicing pronunciation and some of the unique sounds that Arabic uses, and so on) and there’s no real reason why you can’t have this all in the bag before you start formally with the Middlebury programme. If you’re extra enthusiastic, you could learn a bunch of basic phrases that you’ll always need to use — perhaps start with this list — and/or learn the first 500-2000 (depending on your bravery) words in the Arabic frequency list. Either use the versions over at Memrise or Anki for this (both are "no-typing" courses, with audio, I think, so they should be ok for those who’ve just learnt the alphabet). And for a true bonus, pick a teacher over at iTalki and do an easy 30-45 minute lesson every week or two in the winter/spring months before the summer.

Take a look at my last post, and combine with this list for some suggestions on things you could be doing prior to the beginning of the course in June:

- spoken practice via iTalki or some other language exchange site/programme (shout-out to the newcomer Natakallam, which pairs Syrian refugees in Lebanon with Arabic learners, benefitting both parties). From January-early June I was doing 4-5 hours of iTalki lessons every week (an hour session almost every weekday)

- writing practice over at Lang-8 (I’ve written about this before, but basically you write entries (about anything) and people correct them for you in exchange for you correcting things in your native language (presumably English)).

- reading practice — I read through all the Sahlawayhi books from January-June. In case you haven’t heard of this excellent series of graded readers for beginning-intermediate levels (and their paired audiobooks), you’re really missing out. The stories are quirky, and not so difficult that you’re looking up every other word in good ol’ Hans Wehr. Even if the language level in the final levels is beyond what you’re capable of, there’s still lots to devour in the early books. Strongly recommended, though this isn’t really for absolute beginners.

- administrative preparation - Make sure you’ve tied up all your loose ends, as far as you are able. This means delegating work, pausing projects and so on. You might not be able to do this, but try as much as possible. There were some poor souls on the programme who had to work on their 'jobs' on the side of the programme; the amount of homework doesn’t really allow for that and for you to sleep, so one will suffer if you try to continue things from your pre-Middlebury life.

- tools and skills preparation - make sure you’re familiar with Anki, Lang-8 and other such tools before the programme begins. This’ll save you time and headaches that you could be using to learn actual Arabic words, phrases and more. (See below on some of the tools that I consider essential).

- (typing practice - this one’s optional, but given how much you’ll find yourself having to type, I’d strongly recommend you practice this and get comfortable finding your way around the keyboard prior to attending the course, especially at the higher levels where you have to write dissertations of 2000+ words in Arabic (typed, of course). I don’t know of many options for PC-users, but for Mac users you can check out XType (on the Mac App Store) for a structured lesson plan for learning typing using the Arabic alphabet. There’s also Typing Master Arabic available online, but it’s a 100% Arabic-only course so that may or may not be appropriate for you.)

When to Study

Just a quick point here about sleep: it’s really important, especially when you’re cramming words down your throat day and night. Formal classes were usually finished by 3pm, but some people would take time off and only begin homework after dinner at seven or eight in the evening.

I’d strongly recommend you begin your homework immediately following the end of formal classes at 2.30/3pm. This way, you have some work to do after dinner, but it’s not an insurmountable pile of work, and you’re not going to be studying until 3am every day. You can keep up that kind of schedule for a week maybe, but not eight straight weeks of the programme. You’ll either drop out or lose your mind — both, I think, happened this year, to some extent. Don’t be that person.

Try where possible to do the unpleasant / necessary thing now so as not to have to do it later. The Middlebury Arabic programme does not really work well with any kind of procrastination behaviour. Enough said on that.

The Language Pledge

This is quite important, I think. There’s a qualitative difference in terms of how you approach the course if you’re committed to the language pledge and if you’re not.

A lot of people violated the pledge this year (Summer 2015), both on and off campus. I get that it’s sometimes good to let off steam and so on, but if you leave campus and talk English among yourselves, you’re missing out and you’re setting your study back.

(Total beginners aren’t subject to the language pledge, in any case, so don’t worry if that’s you).

Keeping Up with Vocabulary

This is a big one. The course, particularly in the higher levels, is big on encouraging the learning of words. And, in fact, the more I progress in my Arabic studies, the more I think the learning of words (in context, where possible) is perhaps the key thing to progress forwards. This also connects to my final conclusion about Middlebury, that an intensive programme is only useful if you’re taking the things you learnt on into the long-term.

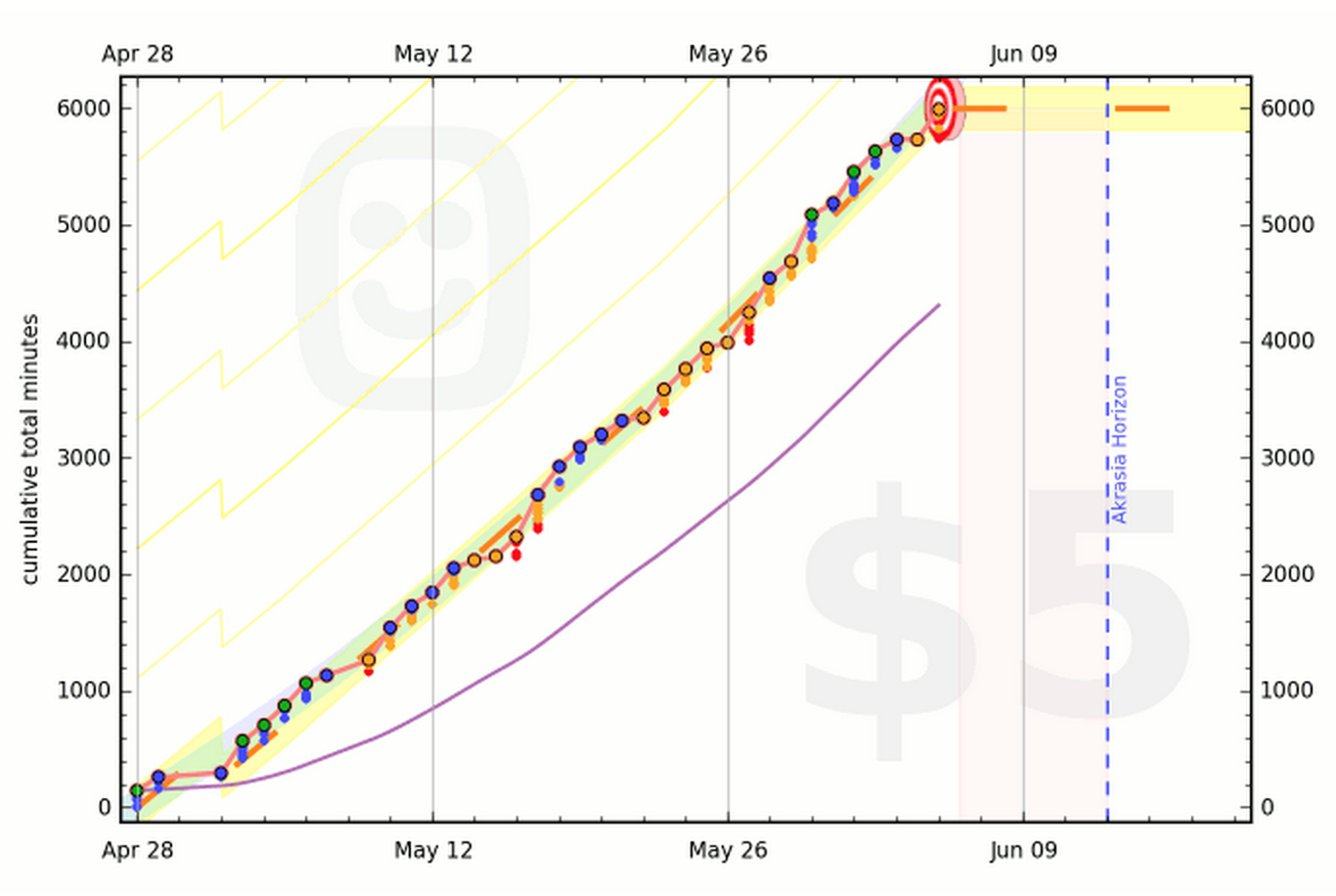

The students of level 4.5 learnt around 3000 new words during the eight weeks of the programme. This doesn’t include words learnt while reading the assigned novel (see below), but I know it’s roughly 3000 because I have them all entered into Anki and I can see exactly how many times I’ve reviewed each one and so on.

Approximately 85 words per day (on each of the five study days per week) is not for the faint of heart. It’s unrelenting and it’s tough and it’s often dispiriting.

I could not have done it without spaced-repetition and my faithful Anki.

If you want to ensure that you’re not panicking every time there’s a weekly vocabulary test, and (more importantly) if you want to make sure that you’ll have a way to keep learning and reviewing the things you learnt while on the Middlebury programme, you have to use some sort of spaced-repetition software. I really don’t see any other way.

Again, I’ve written about spaced-repetition elsewhere so go check that out and then come back.

So now you know that Anki is basically a flash-card programme, one that presents words for review at exactly the right time so you’re not needlessly studying, reviewing and testing yourself on things that you know pretty well. As I said earlier, if you aren’t embracing some sort of software-based approach to storing the things you learn on the course, you’ll just forget it over the months after you leave the programme in which case, why did you pay $13,000 to attend in the first place?

So, to put you in my shoes, every day we’d study new texts, listen to things, write things and sometimes even get vocab lists themselves. Lots of input. After class each day, I’d take an hour (sometimes up to two) inputting the new bits of information into Anki to ensure that I can keep reviewing things during the course without stressing about which words to devote the most time to, and so on.

A typical entry might look something like this: