Matt and I put out a new episode of Sources and Methods podcast today. We spoke to Kael Weston, discussing his time spent living in Fallujah, the importance of speaking the language of the place in which you work, as well as the political systems countries like the USA employ in far-off places like Iraq and Afghanistan. He also recently wrote a book, The Mirror Test, which is worth reading. You can find the episode over on iTunes or listen directly on the Sources and Methods website.

Language

Different Uses for Spaced Repetition

[This is a cross-post via the Spaced Repetition Foundation blog, where it was originally published]

Maybe Spaced Repetition isn't the best word. It's only descriptive after the fact, once someone has explained to you about Ebbinghaus and his experiments learning sheets of random numbers during the 1870s. For a general audience, we probably need a better term to help people understand what you can do with Spaced Repetition. We also need better examples and models of people who use it in a variety of domains of their life.

The first use case or scenario in which many encounter spaced repetition software or uses is language learning. And yes, it is great for learning vocabulary in an efficient manner. You can see how people have found ways to blast through large numbers of words by using things like Anki or Memrise.

But it would be a waste to limit our understanding of what Anki or spaced repetition can do to just learning vocabulary lists. It can be used for so much more. Indeed, expanding people's awareness of the various possibilities is an important reason why Matt, Natalie and I decided to set up this foundation.

With that in mind, I wanted to take a few moments to write down some thoughts on how you can use Anki and Spaced Repetition in other areas of your life. This list isn't in any particular order. You'll find that most things involving information or learning can be somehow coupled with the use of spaced repetition software, and the extent of your use is basically only as limited as your creativity.

- Birthdays -- learn all the birth dates of your friends and family. This probably works best in conjunction with some other system like the major system for remembering numbers, but you might be able to brute force this through.

- Kindle Clippings -- using Anki's in-built cloze deletion tool, you can blank out key parts of your kindle clippings to remind you of things you read in previous months or years. This way, books that you've read needn't be confined to vague memories. You can be more deliberate about what you're learning. Even things like book titles could be something you could learn with Anki. Consider a card which tests me on the author's name and the title (based on a short description). This way I avoid having those moments where I forget the title of the book but remember the contents pretty well.

- Magazine articles / things online as you're reading

I do this a lot. Whenever I'm reading online articles -- in Instapaper, let's say, which is the place where I read most things -- I'll save the highlights of passages I want to keep in my reference library. At a later date, I'll go through those highlights and see what I want to remember for the longer-term. I'll then transfer the clipping or highlight into my Anki library.

- New English words -- I'll occasionally come across technical vocabulary that is new to me while readying. If it's a word that I find myself looking up often, I'll save that entire sentence into Anki and use the cloze deletion method to set up an appropriate test.

- People / Faces

Matt seems to use this far more than me, though I'm starting to do it more often. The idea is that you find a picture of people you meet in meetings or in work contexts (Google Images or Facebook works well for this) and test yourself on their names and maybe one or two key facts about them -- that they're a vegetarian, perhaps, or that they just had a baby, or whatever it is. You can even do this pre-emptively. I once did this prior to a conference/event on Afghanistan. The conference home page had everyone's name and photo (those who were speaking / attending) so I just downloaded the lot, made cards for everyone as well as what their job/specialism was. By the time I arrived at the conference I knew everyone's name and who they worked for and what they worked on. It was a far more relaxed and personable experience than previous events of that kind. I don't get invited to speak at such events any more really, so I have no use for this, but I imagine many readers would find this useful.

- Reference materials -- You probably have things in your life that you're perpetually looking up. The time in-between looking-up probably is a matter of months (or maybe years). Just long enough to forget, but not long enough to forget that you once knew this thing. With Anki, those tip-of-the-tongue moments can become a feature of the past. No more remembering that you once new something.

Some examples: perhaps the precise proportions of a recipe you make every month or two. Yet every time you make the recipe you have to look up whether it is 1 part flour to 2 parts water, or 1:3. Anki can keep your memory fresh.

Similarly with important medical data, or phone numbers, or points of contact for certain work projects or people.

- Coding language -- I used this while studying coding this past summer, and have found it great for making sure that the conventions I learnt for one language didn't get forgotten while I worked on the next language / scenario.

- Revising things you should probably already know but maybe have forgotten

This, for me, is the subject of mathematics. I studied it at school, but since then have had less need for it. This past year I've returned to mathematics with the somewhat embarrassing realisation that even things like my times-tables aren't as solidly in my brain as I'd like. I can tell you what 6x7 produces, but I'll probably need to think about it for a few seconds. Enter, Anki. I've been drilling myself on times tables for a few months and have found a real uptick in the speed at which I can recall those answers.

- Geography

You probably did a certain amount of this at school, but since then haven't added to the knowledge (or some maybe has been forgotten). Learning all the capitals of all the countries of the world (and being able to locate them on a map) isn't just an abstract skill. Things like this enhance your ability to understand and interact with the world. Instead, when you read a news article referencing a number of countries, you can place them on a map and realise that Ouagadougou is the capital of Burkina Faso and that it's included in the article for that reason.

Other niche things I've used Anki to help me with:

- brewing times for different varieties of tea, and also the ideal temperature of the water

- Ayas for the Qur'an (i.e. learning to recite these by heart). I know many use Anki for learning Bible verses, too.

- Learning the periodic table (alas, many years ago, in a deck now since deleted from my phone)

- The Japanese Kanji

Others use Anki for learning med-school data.

As I wrote above, the limit to what you can use Anki for is basically limited only by your creativity and imagination.

Bots: Part of the Future of Language Learning?

Duolingo just released a new feature on their iOS app called 'Bots'. (In case you don't know it already, Duolingo is a really useful free resource for learning a bunch of different languages in a systematic and structured fashion). Their new Bots feature only works for Spanish, French and German languages/courses at the moment.

Their press release included a sample picture (the first one on the left) suggesting the kind of conversation you might have with their bot.

I tried the app out this afternoon, using the French version as I don't speak Spanish (yet). You can see (the beginning of) my conversation in the second image.

What I hadn't realised (and the press release and the deluge of news articles that recycled said press release didn't help with this) was that the app functions on rails. Which is to say, you can't actually have a free-flowing conversation with the bot. You can't even say "I am sad" in the universe of Duolingo's bots. As you can see from the picture above, triste is "not an accepted word".

Clearly this is early days for the technology. It'll get better, and they'll offer it for the rest of their languages and it'll all be wonderful. (Maybe).

I'll be curious to see how people end up interacting with these bots. There have been some great stories / podcasts on how this kind of thing turns out, like the Radiolab 3-parter or the reporting on Microsoft's 'Tay' bot.

And if chatbots increase, so will ways to speak to computers via voice recognition. Different ways of practicing language are to be welcomed, but, as my brief time with the Duolingo bots suggests, it's early early days...

Lessons Learnt: Language Study Habits That Work

I’ve been coaching a dozen or so students for a few months now, and I wanted to reflect a little on the experience. (For more information on what language coaching is, click here). Since I mainly work on meta-skills around habit formation, scheduling and planning, and accountability, I even work with those who are studying languages I don’t speak. (I also work and consult on specific productivity-related issues, such as with PhD students to figure out work plans, idea structures and schedule reconfigurations).

Today, however, I wanted to specifically take stock of the habits and characteristics of the students who have made the most solid progress. (Small caveat / usage warning: All of this is flexible. Most students will do all of these things at some point; the challenge is to make these habits the norm.)

Keep Regular

The key habit that really determines whether you’ll be able to learn a language is studying every day. Students who engage with their chosen target language on a regular basis, even if that is sometimes only for 5 minutes, will do better on average than those who try to wait for the perfect moment to study or who bunch study time into one day of the week. Of course, sometimes your circumstances will make regularity a challenge, but I challenge anyone to tell me that they really don’t have 5 minutes in their day to write some practice sentences. (Even astronauts take breaks.).

Have a Plan

Unless you’ve been learning languages before, this is usually where I come in. You need a macro plan (your goals for the coming year or two) and a micro plan (what you’ll be doing this week or today). There’s often space for a plan for in-between those levels — a few three-month challenges to be accomplished over the course of a year. These goals should be specific and they should be measurable. The smaller short-term goals need to match up with the longer-term goals, and these longer-term goals need to be realistic. (There’s no point thinking you’re going to go from zero to reading modern Arabic literature in 6 months.) There’s a lot more to say about this (a lot of which is best learnt through experience), but for now suffice it to say that you need to know what you’re doing and where you’re going.

Be Flexible

Your goals need to adapt to your life. Life throws up all sorts of surprises and changes, and you need to be able to have the flexibility to change your plans if need be. This doesn’t mean changing your long-term goals every time the wind changes direction or based on momentary enthusiasms and/or distractions. Flexibility means that sometimes the world changes around you (or sometimes you change on the course of your journey) and that you should make sure to take this into account.

Track Your Progress

Having a goal like “become fluent in x” is not a particularly useful goal, mainly because it’s not really concrete enough to be able to monitor your progress. There are many different ways of making your goals concrete, but generally if you can track it in a spreadsheet then you’re probably on the right track. I have all my students track the number of minutes they’re spending working on various skills. They also write qualitative notes on what worked or what didn’t work in a particular session. Anki, the pre-eminent SRS application, tracks a whole bunch of vocal-related numbers as well, which is useful at the beginning since that’s the bulk of the work. Then you can use reviews to see how your day-to-day activities are matching up with your short- and long-term goals.

Plan for the Unexpected

A large number of my students live in Kabul or other countries that face instability, coup attempts and the like. It’s not unusual to get a message like, “I had to move house today because of the kidnapping threat so we’ll have to reschedule today’s lesson.” Or sometimes it’s something mundane like, “There’s no electricity in my part of the city this week.” If you live somewhere like that, you need to plan for the unexpected and for emergency-type situations. This usually means coming up with a list of easy exercises and/or tasks that you can accomplish in 5 minutes or less, or that can be done without any need for electricity or internet. This way, even when you have a bad day and everything is failing around you, you’ve made a plan for such a situation and you can make sure to stay regular.

Break Tasks Down

If you’re living in a chaotic environment, it often helps to break tasks down into smaller components. Even though it’s much better to set aside time (and schedule into your calendar and inform others around you that this is time to be respected), sometimes this isn’t possible. In that case, you can’t just wait until you have an uninterrupted stretch of 60 minutes to study. If you do that, you’ll never study and then you’ll be putting your regularity in jeopardy. So you have to come up with smaller task groupings (that you can accomplish in 10-minute dashes, for example) and you need to be ok with that. A student will sometimes be fine coming up with suggestions for shorter activities, but will strongly resist the idea of studying in shorter bursts. It’s not ideal, but if your life is that chaotic then it might be your only change.

Time

At the lower end of the spectrum, the more time you spend, the more progress you’ll make. This applies to everything from zero to sixty minutes per day. Once you’re studying for over an hour every day without too many exceptions, then it’s time to talk about speeding up the process and making efficiency improvements. But until then, you just need to keep finding time in your day to be doing short small bursts, making sure that it adds up.

Language learning isn’t rocket science. Millions do it every day, the majority without a great song and dance. If you keep in mind these basic principles, you’ll go far.

If you want to work with me on your language-learning goals, please read this overview and get in touch with me using the link specified.

Starting the Spaced Repetition Foundation

When I first learned about the idea of spaced repetition, I felt like I'd discovered a magic trick or a secret of some kind. Here was a piece of research that could transform how quickly I learned new words (I was studying Pashto at the time) and how well I recalled them. On the other side of that elation, I felt a simultaneous frustration and sense of disappointment that this piece of pedagogy / educational science hadn't come up before in my schooling career. All those vocab cards I'd created for my BA degree in Arabic and Farsi! So much inefficiency! Not to mention all the things I had studied at primary and secondary school. Most of that specific knowledge remains but it is like the shadow of its original form. I've recently started studying Maths again and I'm painfully aware just how much I've forgotten.

Spaced repetition is a principle that advocates a specific series of intervals between reviews of a particular fact or 'thing' that you want to memorise. A German scholar called Herman Ebbinghaus discovered that there is a pattern to how most humans learn and forget materials, and he outlined a specific algorithm to ensure optimum recall and retention of whatever you are trying to learn. For that, we must be thankful for the (seemingly) boring experiments he had to go through to get to that piece of insight.

Anki is a piece of software that manages your study and recall of individual pieces of information. The spaced repetition algorithm or insight is at the core of how Anki works and helps you. I've used Anki to learn languages, to memorise smaller facts and useful pieces of information, to cement my understanding of broader concepts, among other things. It's pretty adaptable to whatever your specific learning needs are. This is why I've stuck with Anki over its competitors. (I've tried pretty much all of them, and continue to do so, but Anki remains the most customisable and useful IMHO).

Over the years, I've had the privilege to share Anki with others along my travels. Sometimes this has come in the context of language learning, other times like with the friend who wanted to learn all the names of all the bones in the human body.

In fact, Anki was the original bridge or glue that started my friendship with Matt Trevithick, Sources and Methods co-host and all-round busy person. I walked into his office in Kabul -- he was working at the American University of Afghanistan at the time -- and spied a huge stack of flashcards in a box in the corner. I pointed to them and he explained with great pride how he'd learnt them all. We talked through his process a bit and soon enough I was singing the praises of Anki and how much time he'd save and...and...

We've had many conversations over the years relating to language-learning, the different ways Anki can be used and our overwhelming and continuing sense of disbelief that the principles of spaced repetition aren't more widely adopted in the field of education. People who get deep into self-study eventually stumble on SRS, since you often try to find ways to get faster or better in the absence of a teacher telling you what to do. The Quantified Self movement has been instrumental in spreading the gospel of SRS, too, in their special sessions devoted to the topic in their yearly conference, or through the pride-of-place given to show-and-tell explanations of how SRS has allowed someone to learn Chinese, or hieroglyphics or so on. (Click here for the QS list of talks referencing SRS. I'd highly recommend dipping your toe into some of these talks. Most are extremely engaging.)

Bringing matters up to the present day, I have a bit more time and bandwidth for focus now that the PhD is finished and Matt and I had been talking about this sense that more people should be using SRS for a few years, so we have finally bitten the bullet and started something to try to make that happen.

The Spaced Repetition Foundation is our institutional first step to start to spread the lessons to a broader audience and to more varied contexts. Our mission statement reads:

"The Spaced Repetition Foundation, an independent, not-for-profit center, is dedicated to advancing the adoption of spaced repetition as a supplementary learning tool.

"Despite the scientifically proven ability of spaced repetition to vastly increase the retention of information in the brain as a supplemental learning tool, the use of this technique is, at present, largely restricted to select individuals and students for personal enhancement or academic achievement. To date, no single center exists to advocate for the increased adoption of this approach in educational settings at the macro level, to increase public awareness of this useful tool, and to serve as a focal point for interested individuals to come together and work on these issues.

"Attempting to solve this problem, Natalie, Alex and Matt, long-time users of spaced-repetition applications, decided in the summer of 2016 to start the Spaced Repetition Foundation, which seeks to function as an independent advocate dedicated to increasing the adoption of spaced-repetition technology wherever learning is happening."

Note that we are not completely and exclusively technology-centric in our approach. At least part of the work involves outreach, involves testing use cases and scenarios, and if it really is to find a place in the broader world (away from electricity and flashy phones, perhaps) it must be adaptable to low-tech or no-tech approaches.

Going forward, we'll be spreading the word about the science behind spaced repetition (spoiler: it works), ways everyone can use some form of review-recall testing in their lives, and generally galvanising different communities to find ways to rethink their approaches to knowledge acquisition and long-term recall through spaced repetition. We have some specific first steps planned, but I'll hold off with those details until they are more pertinent.

I'm extremely glad, too, that we will get to work with Natalie McKnight, the other co-founder, who brings a wealth of institutional and practical educational experience beyond simply the solitary learner that Matt and I represent. Natalie is Professor of Humanities and Dean of the College of General Studies at Boston University. I'm excited to work together with her to expand the kinds of communities and settings we can reach.

If you have any interest in the work we're doing, please sign up for our newsletter here or if you are interested in learning more, please do get in touch. Full details are available on our website at http://www.spacedrepfoundation.org.

Svifnökkvinn minn er fullur af álum: Lessons in Icelandic

Yesterday, mostly out of curiosity, I took my first lesson in Icelandic. I’m not anticipating this becoming a major driving force in my life, but I was provoked by someone’s explanation of the language’s pronunciation weirdnesses to learn more.

The alphabet is the same as English (mostly), though there are some new combinations of letters as well as some tricksters that look like you know what they should sound like but that come out as something completely different. Some letters change sounds depending on where they are in a sentence.

The combination of two Ls comes out as a sort of clicking sound. When the two Ls are derived from a foreign word, then it sounds like it might in English. But for everything else – and I’m quoting from my excellent teacher, Thor the Tutor over at iTalki – you want a “wet sound in which the sound of air escapes from underneath and from both sides of the tongue when it’s low in the mouth”. It’s a bit like the combination “TL” in English, except not really.

I also learnt that inhabitants of Iceland have not developed the skill of hearing foreigners speaking their language with bad pronunciation. So while in France or Germany perhaps local / mother-tongue speakers will be able to figure out what you’re saying even if you are butchering the pronunciation, that isn’t the case for Iceland. Luckily, that sets the bar high for pronunciation, which I’ve always held is important to get right from an early stage.

I’d read a little online about the complexities of learning Icelandic:

“The difficulty of different languages manifests at different stages,” Jóhanna says. In Icelandic’s case, taking that first crack at the grammar is daunting. In Icelandic, verbs are conjugated variously for tense, mood, person, number and voice—active, passive or middle. Heavy inflection generates a staggering list of possible ways to say, in one well-known example, the numbers one through four. And although the Icelandic vocabulary has far fewer lexemes than that of a language like English, a single Icelandic word can have a phenomenal range of meanings depending on the particles with which it is used. Consider “halda,” literally “to keep,” which can become “halda fram” for “claim/maintain,” “halda upp á” for “celebrate,” “halda uppi” for “support” and so on.

A textbook I found online had the following caveat to those who sought to embark on a programme of study:

None of this bothers me too much. My teacher said something similar, that the faster we get speaking without necessarily allowing ourselves to fall into the abyss of inflection and grammar then the faster we can progress to the level that it makes sense to add in all the complexity.

By the end of the lesson I was sounding out commonly-used phrases and the trick vowels were catching me out less and less. Now, my task is to learn those phrases and internalise the pronunciation rules through practice. Then I’ll be ready for my next lesson.

Oh, and the meaning of the blog title? My hovercraft is full of eels.

How to become a memorisation and language ninja

I’m very glad to be able to announce two new things I’ve been busy with over the past few months.

Firstly, I’m launching an email course showing how to learn long lists of items by heart. This course is outwardly directed towards Muslims, since the list that you learn over the course of a week, is a list of 99 Names of God — the so-called Asmaa ul-Husnaa. But the broad principles are the same for learning any long list of things, so don’t think you need to be a Muslim to take the course. The materials come with lots of handouts and supplementary information about memory and the like.

Note that this first course is part of something new I’m calling Incremental Elephant, a place where I can offer more courses related to memory, language-learning and productivity.

Secondly, as regular readers of this blog will know, I’ve been blogging about technology, productivity, language learning and the intersection between the three for several years. Along the way, I’ve fielded dozens of questions from readers about which programme to use for this or that scenario, or which textbook to use when starting out with language x or y. I’ve increasingly been taking on longer-term clients to coach through these issues, so I’m taking the opportunity now to announce officially that I offer one-on-one coaching for language learning or productivity-related issues.

The language you’re learning doesn’t need to be one that I already know, because my coaching is usually targeting the meta-issues of how you’re studying rather than what you’re studying.

I offer weekly or biweekly Skype coaching sessions. This will include a mix of reviews of work you did the past week, planning your studies for the coming week and brainstorming techniques to get you over specific problems that are preventing you from moving forward. (For example, I’ve recently been working with someone who has problems declining verbs, so we’ve been tackling that from several angles using a variety of techniques).

More news on the Ph.D. front in a few months, I hope, but for now, go check out the 99 Names course and get in touch if you would like to discuss working with me to improve how you go about learning languages.

UPDATE: I've written up a more extensive explanation of what one-on-one language coaching involves, and what kinds of problems it's best suited to tackling. Read more here.

On Untangling Syria's Socially Mediated War

How do we figure out what is going on in a country like Syria, when journalists, researchers and civilians alike are targeted with frustrating ease? Is it enough to track what is being posted on social media outlets? These two questions are at the core of a fascinating recent(ish) study published by the United States Institute for Peace (USIP).

Syria’s Socially Mediated Civil War – by Marc Lynch, Deen Freelon and Sean Aday – came out in January 2014 and analyses an Arabic-and-English-language data set spanning a few years. It offers a useful overview of the social media trends as they relate to the ongoing conflict in Syria. It is especially relevant for those of us who aren’t inside Syria right now, and who are trying to understand things at one remove, whether that is through following social media output or talking to those who have left the country. (This means journalists, researchers and the like.)

Some stark conclusions emerge from the report. The ones I’m choosing to highlight here relate to how international media and research outlets have often been blind to structural issues that obscure their ability to understand Syria from outside the country.

“Social media create a dangerous illusion of unmediated information flows.” [5]

The role of translation or the importance of having research teams that are competent in both English and Arabic comes out very strongly from the research.

“The rapid growth in Arabic social media use poses serious problems for any research that draws only on English-language sources.” [page 3]

The report details how tweets about Syria in Arabic and English came to be different universes, how the discourse rarely overlapped between the two and that to monitor one was to have no idea of what was going on in the other:

“Arabic-language tweets quickly came to dominate the online discourse. Early in the Arab Spring, English-language social media played a crucial role in transmitting the regional uprisings to a Western audience. By June 2011, Arabic had overtaken English as the dominant language, and social media increasingly focused inward on local and identity-based communities. Studies using English-only datasets can no longer be considered acceptable.” [6]

Also:

“The English-language Twitter conversation about Syria is particularly insular and increasingly interacts only with itself, creating a badly skewed impression of the broader Arabic discourse. It focused on different topics, emphasized different themes, and circulated different imagery. This has important implications for understanding mainstream media’s limitations in covering Syria and other non-Western foreign crises and raises troubling questions about the skewed image that coverage might be presenting to audiences.” [6]

Also:

“researchers using only English-language tweets would be significantly misreading the content and nature of the online Twitter discourse.” [17]

And:

“These findings demonstrate once again the insularity of English-language journalists and the rapid growth of the Arabic- speaking networks. Both findings are potentially troubling for at least two reasons. First, they imply a journalistic community whose coverage may be influenced more by its cultural and professional biases than by the myriad constituencies within Syria and across the region. Second, they point to the power of social media to draw people into like-minded networks that interpret the news through the prism of their own information bubbles.” [26]

The general ideas in here won’t necessarily come as a surprise but I found it instructive to see just how different those two discourse universes are in the report.

In a separate but not-unrelated note, I have been thinking of ways that I can stay engaged in what’s going on in Syria beyond just consuming reports at one step removed. I’m working with a beta-testing team using a piece of software called Bridge – made by the lovely team at Meedan – which allows for the translation of social media and the use of those translations as part of an embedded presentation online. I will be translating strands and snippets from certain parts of Syria’s social media universe in Arabic. More on this soon, I hope.

Ecolinguism and the ethics of learning new languages

I was interviewed by Tammy Bjelland of the Business of Language podcast a few weeks ago, and the episode recently went live. Readers of this blog will know that I write about the study of language with some regularity – see the archives for some previous posts – but I don’t talk about it a great deal on my own podcast nor is it really the focus of my work. So it was nice to have a chance to talk through my background in learning languages and the challenges of learning languages with few materials available for self-study. There isn’t enough written about this.

It was also gratifying to find a forum to discuss Richard Benton’s ideas about ecolinguism. He wrote a blogpost summarising some of his ideas here:

I am an ecolinguist because I want my work to preserve the complexity of our world’s language and culture ecosystem. How do you create a strong community made up of hardened, poor refugees and rich, privileged natives? The privileged must work hard to create new connections. In middle school, the band geek or math nerd can’t simply decide to enter the “cool crowd.” Only those with strong social capital can invite in those on the outside.

The strength of our communities depends on the decisions of the privileged and the powerful. When insiders opt to forgo their comfort to commune with those who go without, they unite communities who would be isolated. When a well-educated privileged professional chooses to learn a language, for example, he forgoes his advantage in communicating in way where he feels most comfortable. The white Minnesotan, speaking elementary, broken Somali, puts the outsider, the refugee, in the position of power. Struggling to learn this difficult language allows new connections to grow.

The choices we make as to which language to learn next have a broader impact beyond our own lives. For the full discussion, visit Tammy’s website to listen to the full episode or subscribe via your preferred podcast client.

UPDATE: I now offer one-on-one language coaching. Read more about what it involves and what kinds of problems it's best suited to addressing.

How to Survive Middlebury's Arabic Summer School Programme

[UPDATE: I now offer one-on-one language coaching designed to help students prepare for Middlebury's intensive summer programme. Read more about what it involves and what kinds of problems it's best suited to addressing.]

[UPDATE 2: (Jan 2017) I've just finished writing a new book, Master Arabic, on getting from an intermediate level in Arabic to advanced. Read more here.]

I returned from my summer course in Middlebury a few weeks ago, and I thought it might be worth writing up a few of my thoughts about the programme, whether I’d recommend it to others studying Arabic (and other languages) along with some other more practical tips for students who will be joining the summer programme in the future.

Overall, I had a good time and I learned a lot. I think that alone should be sufficient recommendation. It’s two months where you get to study something to the exclusion of everything else, so in that sense it’s a real chance to focus, to immerse yourself in the skill. To some extent, the programme almost could have been anything at all and students would benefit, especially if you’re able to work alone and at the level where you’re able to profit from self-directed study. I can’t remember the last time when I focused on one thing and one thing only over a period of two months. I was also really lucky to have two excellent teachers leading our class, and to have been awarded one of the we-pay-for-everything Kathryn Davis fellowships; for both, I’m extremely grateful.

You can read more about the programme itself here but basically, it’s an eight-week programme of intensive language instruction and practice. They implement a language pledge (to read more about my implementation of that, read this) which means for the entire duration you’re not supposed to talk or use any other language than your target language (Arabic, in my case), even when outside the classroom. I took it a step further and stopped using anything other than Arabic on twitter, email and so on.

One of the interesting (sometimes frustrating) features of the Arabic language is the so-called 'diglossia' (and here). This means that the language used in writing and in conversation in the mass media and among educated Arabs is different from the more colloquial spoken or dialect version of the language. For the beginner, this is a frustrating realisation, especially since so few programmes and textbooks seem to place much emphasis on learning the colloqial/spoken part of the language. When I studied at SOAS (the BA Arabic programme) there was virtually no emphasis placed on the dialect, aside from the year abroad (which I spent in Damascus and thus had some contact and exposure to the Syrian / shami dialect). In any case, I was expecting that the Middlebury course would have more to offer in terms of dialect tuition, especially having spent hours reading their website and course syllabi, but this was not the case. There are dialect classes four days per week, but they are not taught to any particular syllabi and it very much is a question of chance as to whether your teacher knows how to teach (and encourage the practice of) their dialect or not. The only thing I’d say, though, is that there are lots of varieties on offer, from the more common Egyption and shami to Jordanian, Moroccan and even Sudanese. Anyway, this is all just a warning to say probably don’t go to Middlebury if all you care about is developing a really good set of spoken skills.

Students take a long placement exam the day after they arrive, and then the 140-or-so of them are split into levels. Normally four is the highest level offered, but this year they added 4.5 to accommodate people who had slightly longer experience/exposure. (I was in that class).

Formal classes run from 8.45am-1:15pm (with some 5-15 minute breaks in-between to space it up) followed by lunch. After lunch, there are colloquial / dialect classes for an hour, and then you more or less spend the rest of the day doing assigned work in preparation for the next day, revision of the work you did that day and other kinds of homework. I think the teachers estimate that you should be doing four or five hours of work outside class every day, or that’s what they aim to provide/assign. That’s what’s meant by the whole "intensive" part of the Middlebury programme. (For more on whether I found the intensity of the programme useful, see below).

What follows consists of recommendations for those planning to take the programme in the future. It’s mostly things I did while I was on the course, but there are some things that I’ve since realised would have been useful as well or instead of the approach I took. Feel free to pick and choose which sections you read, as they’re all meant to more or less stand alone, depending on your interest.

Preparation

I’ve already written up some thoughts, here, on what I did before the programme started to ensure that I wasn’t just revising things I had already studied. My case was perhaps unusual in that I had a long period of (somewhat-focused) study under my belt in terms of my BA degree, but years of non-use meant that I didn’t really feel confident using the language any more.

Why is it useful to do some extra study before the start of the course? I’m going to take it as a given that you’re not a complete beginner, in which case, you more or less know what you need to be studying: a little bit of grammar perhaps, lots and lots of words, lots of spoken practice, a decent amount of reading at the appropriate level, and so on. So why not get a headstart and do some study beforehand so you can benefit from the focused months coming your way?

If you’re a complete beginner, there’s still a lot of value in doing some work before the programme starts. A lot of the things you do in the early days of learning Arabic are somewhat menial (learning the alphabet, practicing pronunciation and some of the unique sounds that Arabic uses, and so on) and there’s no real reason why you can’t have this all in the bag before you start formally with the Middlebury programme. If you’re extra enthusiastic, you could learn a bunch of basic phrases that you’ll always need to use — perhaps start with this list — and/or learn the first 500-2000 (depending on your bravery) words in the Arabic frequency list. Either use the versions over at Memrise or Anki for this (both are "no-typing" courses, with audio, I think, so they should be ok for those who’ve just learnt the alphabet). And for a true bonus, pick a teacher over at iTalki and do an easy 30-45 minute lesson every week or two in the winter/spring months before the summer.

Take a look at my last post, and combine with this list for some suggestions on things you could be doing prior to the beginning of the course in June:

- spoken practice via iTalki or some other language exchange site/programme (shout-out to the newcomer Natakallam, which pairs Syrian refugees in Lebanon with Arabic learners, benefitting both parties). From January-early June I was doing 4-5 hours of iTalki lessons every week (an hour session almost every weekday)

- writing practice over at Lang-8 (I’ve written about this before, but basically you write entries (about anything) and people correct them for you in exchange for you correcting things in your native language (presumably English)).

- reading practice — I read through all the Sahlawayhi books from January-June. In case you haven’t heard of this excellent series of graded readers for beginning-intermediate levels (and their paired audiobooks), you’re really missing out. The stories are quirky, and not so difficult that you’re looking up every other word in good ol’ Hans Wehr. Even if the language level in the final levels is beyond what you’re capable of, there’s still lots to devour in the early books. Strongly recommended, though this isn’t really for absolute beginners.

- administrative preparation - Make sure you’ve tied up all your loose ends, as far as you are able. This means delegating work, pausing projects and so on. You might not be able to do this, but try as much as possible. There were some poor souls on the programme who had to work on their 'jobs' on the side of the programme; the amount of homework doesn’t really allow for that and for you to sleep, so one will suffer if you try to continue things from your pre-Middlebury life.

- tools and skills preparation - make sure you’re familiar with Anki, Lang-8 and other such tools before the programme begins. This’ll save you time and headaches that you could be using to learn actual Arabic words, phrases and more. (See below on some of the tools that I consider essential).

- (typing practice - this one’s optional, but given how much you’ll find yourself having to type, I’d strongly recommend you practice this and get comfortable finding your way around the keyboard prior to attending the course, especially at the higher levels where you have to write dissertations of 2000+ words in Arabic (typed, of course). I don’t know of many options for PC-users, but for Mac users you can check out XType (on the Mac App Store) for a structured lesson plan for learning typing using the Arabic alphabet. There’s also Typing Master Arabic available online, but it’s a 100% Arabic-only course so that may or may not be appropriate for you.)

When to Study

Just a quick point here about sleep: it’s really important, especially when you’re cramming words down your throat day and night. Formal classes were usually finished by 3pm, but some people would take time off and only begin homework after dinner at seven or eight in the evening.

I’d strongly recommend you begin your homework immediately following the end of formal classes at 2.30/3pm. This way, you have some work to do after dinner, but it’s not an insurmountable pile of work, and you’re not going to be studying until 3am every day. You can keep up that kind of schedule for a week maybe, but not eight straight weeks of the programme. You’ll either drop out or lose your mind — both, I think, happened this year, to some extent. Don’t be that person.

Try where possible to do the unpleasant / necessary thing now so as not to have to do it later. The Middlebury Arabic programme does not really work well with any kind of procrastination behaviour. Enough said on that.

The Language Pledge

This is quite important, I think. There’s a qualitative difference in terms of how you approach the course if you’re committed to the language pledge and if you’re not.

A lot of people violated the pledge this year (Summer 2015), both on and off campus. I get that it’s sometimes good to let off steam and so on, but if you leave campus and talk English among yourselves, you’re missing out and you’re setting your study back.

(Total beginners aren’t subject to the language pledge, in any case, so don’t worry if that’s you).

Keeping Up with Vocabulary

This is a big one. The course, particularly in the higher levels, is big on encouraging the learning of words. And, in fact, the more I progress in my Arabic studies, the more I think the learning of words (in context, where possible) is perhaps the key thing to progress forwards. This also connects to my final conclusion about Middlebury, that an intensive programme is only useful if you’re taking the things you learnt on into the long-term.

The students of level 4.5 learnt around 3000 new words during the eight weeks of the programme. This doesn’t include words learnt while reading the assigned novel (see below), but I know it’s roughly 3000 because I have them all entered into Anki and I can see exactly how many times I’ve reviewed each one and so on.

Approximately 85 words per day (on each of the five study days per week) is not for the faint of heart. It’s unrelenting and it’s tough and it’s often dispiriting.

I could not have done it without spaced-repetition and my faithful Anki.

If you want to ensure that you’re not panicking every time there’s a weekly vocabulary test, and (more importantly) if you want to make sure that you’ll have a way to keep learning and reviewing the things you learnt while on the Middlebury programme, you have to use some sort of spaced-repetition software. I really don’t see any other way.

Again, I’ve written about spaced-repetition elsewhere so go check that out and then come back.

So now you know that Anki is basically a flash-card programme, one that presents words for review at exactly the right time so you’re not needlessly studying, reviewing and testing yourself on things that you know pretty well. As I said earlier, if you aren’t embracing some sort of software-based approach to storing the things you learn on the course, you’ll just forget it over the months after you leave the programme in which case, why did you pay $13,000 to attend in the first place?

So, to put you in my shoes, every day we’d study new texts, listen to things, write things and sometimes even get vocab lists themselves. Lots of input. After class each day, I’d take an hour (sometimes up to two) inputting the new bits of information into Anki to ensure that I can keep reviewing things during the course without stressing about which words to devote the most time to, and so on.

A typical entry might look something like this:

which will, in due course, create cards like this, to test my recall:

(That card is giving me a picture of a political prisoner along with the context of a sentence in which a word (mu3taqaliin) was originally present; it is my job to remember which word is suitable for that context, prompted by the picture to remind me. Note that the cards are 100% Arabic-only. This is important in general, regardless of the Middlebury language pledge.)

(By the way, this method of 100% target-language-only cards, and the formatting of the cards and a lot of the 'system' I’m describing here draws heavily on the system described by Gabriel Wyner in his fantastic CreativeLive course on learning languages. I’ve recommended that in the past, too.)

So I’ll do that for every new word we learned, sometimes formatting them those context-heavy cards, and sometimes cards without the context (especially when first learning a word, and when the word or phrase is something tangible). Like this:

…which is a prompt for me to recall the Arabic word for "hummingbird" (which I saw fly by me one day while walking around the grounds of the campus). When I click the card to check the answer, I also hear the word pronounced.

For words I’m learning for the first time, or for really abstract terms that I can guess are going to have a complex usage within different contexts, I would then write out — I still do all this, by the way, every time I learn a new word — a sentence or two to check that I’ve really grasped the meaning of the word and how to use it in the context of the real world. At the end of my study session, I’ll post all my new practice sentences over on Lang-8, and usually within about two or three hours they’ll all be corrected. I’ll then take the corrections, add them into Anki so now I have:

1) words presented without context

2) words presented with the context of whatever text we were studying at the time

3) words presented with an entirely new context, one which has personal relevance and immediacy to me because I wrote it.

This is how you learn lots of words.

If you’re not keen on posting things to lang-8, just take your practice sentences to your teachers during office hours each day (usually around 9 or 10pm) and get them to correct them together with you. Straight after you’ve been to see your teacher, go add those corrections into Anki so you can be tested on them (see more on this in the next section). Our teachers were happy to see students doing this, practicing the new words in context and seeing people taking the extra effort to master the material.

So if you’re doing this, you’ll actually be studying some hundred or so new cards every day — sometimes more, if you include the new words you study during colloquial classes — and in order to keep on top of this, you’ll need to start reviewing first thing every day. Seriously, just get up at seven in the morning and spend an hour every day before class reviewing the cards that Anki selects for you. Do another hour in the afternoon/evening and you’ll on the right path. It seems a lot, but the payoff is amazing. (I usually was reviewing Anki cards between 1-3 hours every day, depending on how many words I had added the previous day) throughout the eight-week period.)

(Side-bar: If you’re in a class that likes to work/collaborate together, you can — of course — spread out the workload of inputting words into Anki, and then everyone can benefit from sharing the files).

The night before tests, I would often see people around campus 'cramming' words, and the next morning I’d hear about how they were studying until 4am and so on. This is not a recipe for success in the long-term. This won’t help you retain the words after the course ends.

So start using spaced-repetition software and make it more likely that you’ll remember the things you learn…

Learning from Homework Corrections

I mentioned this in the previous section. The Middlebury course includes a decent amount of written homework every day (particularly in the higher levels). If you’re not finding some way of systematically reviewing the mistakes you made (after you get your corrections back), then you’re really missing out. In fact, you might as well not bother doing the homework if you’re not going to bother reviewing the corrected versions.

It works something like this. I’ll do it in English so you can see what I mean. I’d write a sentence like this, perhaps:

I go to the supermarket last week.

The phrase "last week" alerts us to the fact that the verb should be in the past tense. Thus, the corrected version should be:

I went to the supermarket last week.

So I’ll have a card that prompts me with:

I __ to the supermarket last week.

I’ll probably also have a picture of someone walking or "going" alongside that prompt, and the correct answer will be "went".

I made cards for every single homework correction or sentence where there was a mistake. Again, inputting it all can take a good chunk of time, and I would only input one or two instances of each error (i.e. if I misspelled the same word thirty times in an essay, I wouldn’t make thirty different cards testing the spelling of the word), but it saves time in the long-run. This is the speedy way to excise commonly-made errors from your life.

Learning Grammar

I approached grammar slightly differently during the Middlebury course. By the time you’re at level 4.5, you’ve already studied all the basic grammar you’re ever going to need, probably more than once. So the grammatical points we studied were a mixture of revision of the basics and some obscure aspects of the language.

Again, I’d make sure I wrote sample sentences practicing the grammar points under discussion and those would (post-corrections) make their way into Anki. If there were lists of things to be learnt — the seven forms of the siffa mushabahha, for example — I’d make a card that asks me for those seven forms, then I’d pick sample words in those verbal forms, then add them to a memory palace, and then the Anki system would keep reviewing my command of those seven forms. (Don’t worry if the details of what I just wrote were incomprehensible; just take away the fact that I was finding ways to test myself on the grammar we learned, in abstract form (i.e. a list of the forms) as well as in applied form (sample sentences using the things I’ve learned in real-world context).

Readings

Another thing the Middlebury course — like any decent language programme — includes a lot of is reading. Where possible, I used Steve Ridout’s excellent online service called Readlang.

I’ll let Steve explain the overall principle:

Now you know how Readlang works, you’ll have figured out why it’s such a valuable service. You read texts, you figure out the words you don’t know, and then you test yourself on those words using the context of the passage you just studied (and testing employs the spaced-repetition algorithm, too!). Readlang also allows you to export your 'learned' words into Anki.

There are some slight amendments I’d recommend for Arabic-learners. If you go to your account settings you’ll have the opportunity to enter in details for a custom Arabic dictionary. Delete whatever is the default there at the moment (probably Google) and use the following text to refill the form.

URL: http://arabic.britannicaenglish.com/en/{{query}}

It should look something like this:

It’s one of the best online dictionaries for Arabic and works very well in conjunction with Readlang.

Colloquial/Dialect Classes

I don’t have too much to say about these. If your colloquial class teaches you a lot of new words, make sure to add them all to Anki and review as appropriate. You’ll probably have to pronounce the words yourself when making new cards — this explains the basics of how to do that — so make sure to make annotations on class handouts as to the vocalisation of the words (i.e. the vowelling) so that you’re not mispronouncing.

The Novel

We read Tayyib Saleh’s Mawsim al-hijra illa al-shomal ('Season of Migration to the North’) over the course of the eight-week programme. It’s not particularly long, but the language used is difficult, especially in terms of the huge number of new words.

The idea of studying a novel in the context of the Middlebury programme — as explained by the director and by our teachers — is exposure. Exposure to grammatical structures, exposure to phrases, exposure to culture, and exposure to vocabulary. You aren’t really meant to be learning all the new words, just trying your hardest to figure out what’s going on in the context of the story.

I used Readlang (along with a copy of the original Arabic text of the novel) to read the assigned chapters each week. That way I wasn’t spending all my time looking words up in Hans Wehr. The number of new/unknown words made that an untenable prospect.

I also got hold of an audio-recording of the text of the novel. This will be tricky to do, but it really pays off. As you may know, it’s hard to read a passage out loud in Arabic if you don’t know the meaning of the words and — sometimes — the grammar of the passage. (This has to do with how the language works). I’m also a fairly slow reader, so having an audio recording of the passages being studied is a real help.

I’d usually listen to the audio of the section due for a particular week’s study once or twice before even starting with the reading. Then I’d use readlang and go through line by line. And then I’d listen to the chapter another time, sometimes several times.

You’ll find it difficult to find recordings of novels in Arabic. For some reason there isn’t a market for them, and nobody is producing recordings, so you’ll probably have to make your own. This may involve asking your teacher on iTalki to do it (this is what I did), or asking a freelancer on Upwork or any of the many thousands of contracting/freelancer sites. Or just post a request on Facebook perhaps. You’ll probably be able to get it done for under $100, which in the context of your investment into the Middlebury programme isn’t actually a great deal, even more so if you split the cost between the members of your class and share the audio recordings.

Getting your hands on an audiobook version of the novel you’re studying is something I’d really strongly recommend.

Poetry Night

Towards the end of the programme, the course organizers put on an evening of poetry recitation. Students are given the opportunity (a few weeks earlier) to volunteer to recite a poem as part of the evening’s activities. It’s a long evening, and amongst all the other work you are busy with on the course, it’s hard to see why you’d volunteer to take on another burden, but it’s well worth it. It’s a chance to expose yourself to (often) highly stylized language. It’s a change to really polish your pronunciation. And, by the time you’re done rehearsing, you’ll probably have memorized the text so it’s also a chance to learn a poem in Arabic by heart. I recorded my recitation on that evening here. Apologies for any mistakes etc.

Further Online Resources

- Context-Reverso — I have one of my fellow classmates to thank (Hi Yasmine!) for this gem. You put in a word, and it spits out example sentences (drawn from a big database of sample real-word texts) using that word in context. For the intermediate-advanced learner, it’s an amazing resource, far more useful than Google Translate or any others of its kind.

- iTalki — I mentioned this above, especially in the context of your preparations for study at Middlebury. I also (where classmates were off campus on weekends, or in order to prepare for oral presentations and so on) scheduled one or two lessons during the programme itself so that I could talk through my ideas, or a difficult piece of text etc, with my teacher over Skype.

- Lang-8 - I mentioned this above. Use it. Love it. Share it.

- Electronic Hans Wehr — You can search the Hans Wehr dictionary online by root.

- Forvo — great for getting audio pronunciation of words for use in your Anki deck.

Conclusion: How useful are intensive language study programmes?

I’m not sure how useful the "intensive" part of the Middlebury programme really is. Most students didn’t have a system to manage the massive levels of input, so a lot of their time and efforts were wasted. If Middlebury taught and offered ways for students to be better prepared — such s some of the things I’ve attempted to outline above — then perhaps I’d feel more charitable to the programme, but as such I feel many students were let down in some way.

So, after all that, was it worth it? On balance, yes, but mainly because I didn’t have to spend all that money for the course fees (on account of my scholarship) and also because I had systems in place to ensure that I wouldn’t forget the things that I was learning during the course.

If you’re a complete beginner and want to leapfrog ahead to the point where you can start teaching yourself, I’d recommend this programme. If you’re already at intermediate levels, you might want to look into other ways, especially if you aren’t lucky enough to have an employer or a grant that pays for your attendance.

I’ll be writing a separate post on resources available to the intermediate-advanced Arabic language student in due course, as well as on how to get out of the plateau into which it’s easy to find oneself. Till then, I hope you found this useful…

Arabic Language Update: I did it! (Almost)

Just a short post as I'm off away on an intensive language course for most of the next three months. This is the programme run by Middlebury College, but held in Oakland, California (USA) at Mills College. I was extremely lucky to win a Kathryn Davis Fellowship which covers the costs of the course and food and accommodation while I'm there. I have a BA degree in Arabic and Farsi from London's School of Oriental and African Studies, but 10 years in Afghanistan spent writing books and studying Dari and Pashto meant that my Arabic has atrophied considerably. I thought it was time to resurrect those old skills, in part as a way of deepening my understanding of some of the religious aspects of the Afghan Taliban and in part -- let's be honest here -- as a way of covering my bases prior to Afghanistan completely falling off the map a few months from now.

I'll be writing a much longer post on how to get a high-beginner-to-mid-intermediate level out of the well-known "intermediate language plateau" after the course finishes, specifically focusing on what resources are available to Arabic-language students who have good basic skills but want to go beyond that to more advanced materials. (Read these three posts for more on getting out of language plateaus in general terms.)

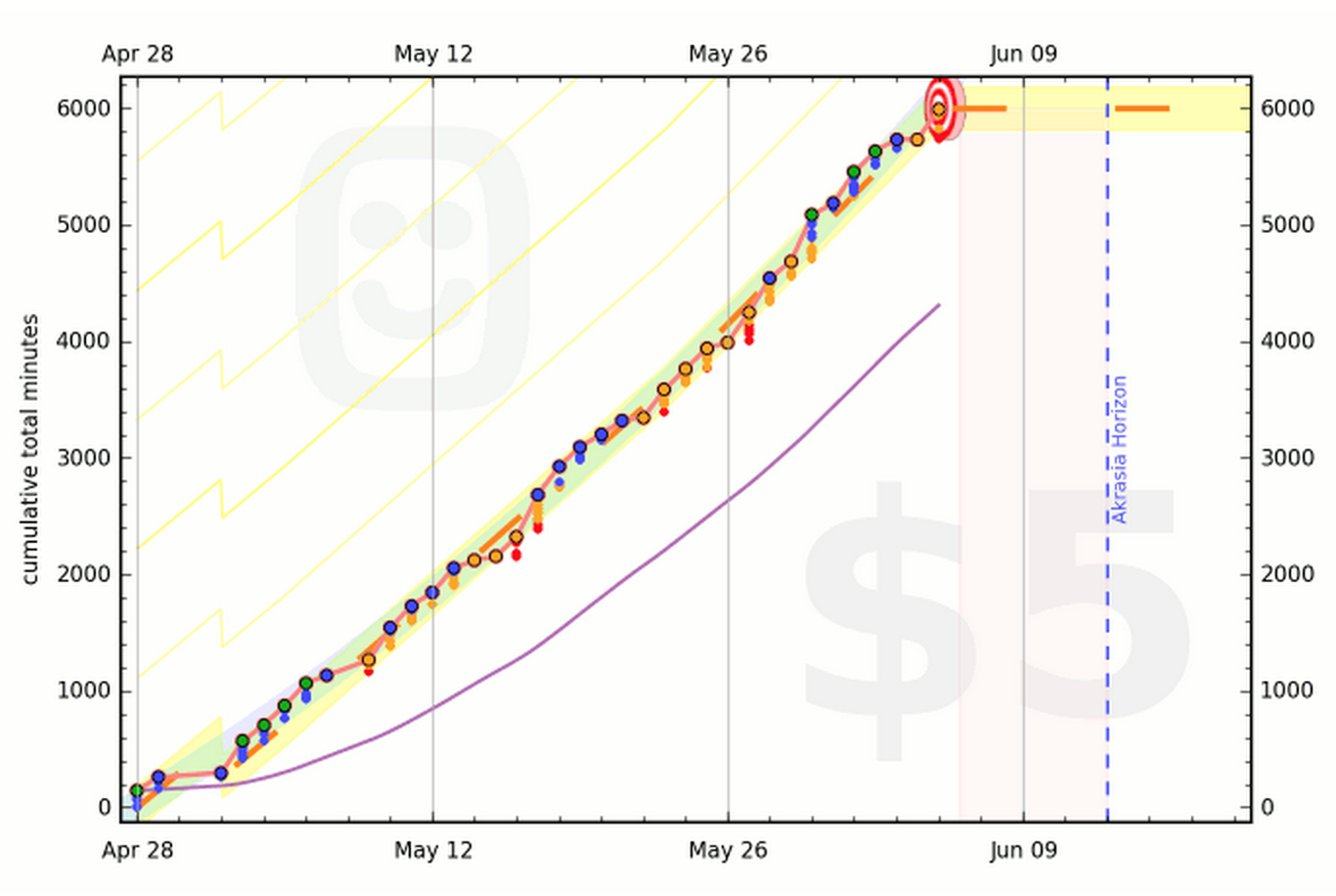

The Middlebury course caters to various levels of language ability, and since I didn't want to waste the opportunity just revising things I had already learnt at university, I had to do a good deal of preparatory work these past few months. I started getting serious about this preparation in February. This involved over 75 hours of spoken/conversation practice (and some grammar work) with a number of different native Arabic speakers over Skype (lessons made possible through iTalki.com), as well as a lot of reading and listening. In June, as you can see on the Beeminder graph displayed above, I challenged myself to get 100 hours of exposure to the Arabic language over a period of 30 days; this included some iTalki lessons, but was also a lot of listening to Arabic-language podcasts, time spent writing on lang-8 and lots of time spent doing so-called "extensive reading" (much more to follow on that in August/September). I managed 99.5 hours, in total, just short of the total required to successfully complete the challenge I'd set myself, but enough to really make my language proficiency come along in leaps and bounds.

An additional note to those who would like to get in touch with me during this period: as part of the Middlebury course, they expect participants to take a language pledge where you only speak the language of study (i.e. Arabic for me) for the duration of the period of study. Read more here. For non-Arabic speakers, if you want to get in touch with me, please visit Google Translate and translate your message into Arabic there before copying the full text and pasting that into the email. It's not perfect, but it allows me to continue to stay connected with the world without violating the language pledge. If I reply, I'll be doing that in Arabic, too, so you'll have to copy the text back into Google Translate to get a sense of what I replied.

I'll be away on the course until the end of August, and will thus ignore all non-essential email until then. If you write to me in English, I will also ignore your email until September. Thank you.

UPDATE: I now offer one-on-one language coaching. Read more about what it involves and what kinds of problems it's best suited to addressing.

Urdu Frequency Dictionary

An Ankified Urdu Frequency Dictionary

Until recently I had been trying to spend more time in Pakistan's megatropolis, Karachi. As part of this move I had been trying to learn Urdu. There are a variety of excellent study materials for Urdu, but I won't write about those today. Rather, I want to offer up a resource for serious students of the language.

Readers of my previous language posts will know about Anki. For those who don't know, it's basically software that allows you to memorise pieces of information (such as foreign language vocabulary).

Frequency dictionaries are wonderful things. They present words of a language in the order of frequency used (usually in writing). They are assembled by amassing huge databases/corpora of text and these are analysed to see which words are used most often.

For a beginning learner of a language, they can be a real help. You start with the most frequently used words and work your way out to the ones you'll encounter less.

Nothing like this exists for Urdu. Or so I thought. I was passed a series of scanned PDF images of an old frequency dictionary published in Canada in 1969. This was made on the basis of an analysis of newspaper copy/texts. Obviously the language used is a bit dated, but as a solid start, this is a good selection. (For those with deep pockets, you can search bookfinder.com for "An Urdu Newspaper Word Count" by Mohammad Abd-Al-Rahman Barker but I'll warn you that the cheapest copies available are $100+ USD).

Unfortunately, in the part of the dictionary I was sent, the words are listed in alphabetical (by Urdu) order. This means that the order is not ideal. There are, however, 9,956 words in this collection. If you're serious about Urdu you could do a lot worse than learning all of them. You'll skew your vocabulary a little towards the literary side, but that's not necessarily a bad thing.

I had someone type up the whole dictionary into Anki and add a spoken audio file for every word. (Many thanks to Affan Ahmad for this massive labour.) You can even set Anki to deliver you words randomly served from the frequency dictionary.

So, without any further ado, the files are here. They are split up because Anki became a bit difficult when inputting the files, but you can combine them on your own computer into a single "Urdu" folder.

Enjoy! And please post any feedback below in the comments. I mainly wanted to get this out into the public so people can use it (rather than gathering dust on my laptop).

UPDATE: I now offer one-on-one language coaching. Read more about what it involves and what kinds of problems it's best suited to addressing.

How to learn a language to fluency: interview with Gabe Wyner

Gabe Wyner has a book out today, and I took the time to interview him about his method. It relies on several things I've mentioned on this blog before -- namely Lang-8, Anki, spaced repetition, mnemonics etc -- so I'm trying out something new: posting the audio of the interview I did a few days ago.

Gabe's book is worth your time, especially if you're getting back into learning languages, or if you're starting for the first time. If you have less patience for books and the written word, you can watch his course over on CreativeLive. It's 18-hours of instruction (in an classroom environment) on how to learn a language using his method. All the steps outlined in his book are expanded upon in this course. I have watched it all, and can attest to its value.

The interview can be listened to here.

UPDATE: I now offer one-on-one language coaching. Read more about what it involves and what kinds of problems it's best suited to addressing.